User:Jarred

Hi, I am Jarred Glickstein Find me on my website and on The Thingiverse.

Contents

Blog 7: Research Equipment

I think the idea of more accessible lab equipment for developing countries or to save money regardless is a worthwhile venture. I would however not immediately seek the use of a 3D printer to make all lab equipment necessary until it is assessed what should and should not be printed. With that said, I cannot think of any lab equipment we have printed. I have made a dremelfuge, a 3D printed miniature centrifuge found here, as well as a graduated pipette but have not made anything at this school.

As for the printable AFM nanoscope, I would be hesitant to call it "printable" as the entire thing is not comprised entirely of plastic parts. I think a good 3D printer could produce useful parts for such a device, but it is important to also realize not everything is best made on a 3D printer, especially as far as precision laboratory equipment is concerned. The open source nature is critical for it to be accessible to people in many places. Some people may want to build some parts out of different materials, and with the source plans for the products available, it makes it possible for people anywhere to bootstrap the process of building the device. I think the importance is this accessibility

Anyone with access to the tools used to make the nanoscope (Legos and a 3D printer) could also make the actual designed device. While I would question the accuracy of printed parts, I know parts can be made with good accuracy. If this was not open source, it would not be accessible to smaller communities. As the first article mentions, large companies charge high prices for a lot of their products. Open source laboratory equipment which can compete with the expensive corporate products can provide access to these smaller communities. It could also help ease budget stress in any laboratory and give hobbyists around the world access to lab equipment.

Blog 6: Direction of Future Projects

One of the most significant ventures to explore moving forward is dual extruders. My interest in dual extruders lies in the potential for using a dissolvable support material to print extremely complex objects. Currently we are limited by overhangs and other structures which are not deemed printable. In many cases, we can worth through those challenges by designing parts to be printable. In my personal work, I am often faced with a need to print parts for myself which would be difficult to design as printable. More often I am asked by other people to print parts which are difficult to print, but I am unable to tell the person I am printing for that he or she needs to come up with a different model for it to be printable. It is my hope that dual extruders would let us push past that.

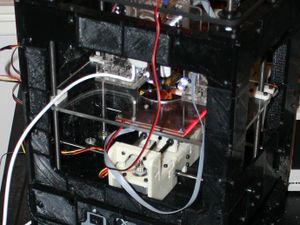

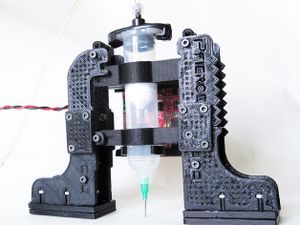

Plastic extruders jam a lot (in my experience, but mileage may vary). They have a variety of benefits and drawbacks, which similarly influences my above statement that some things are printable and others are not. If we invest time in syringe extruders, we will be able to work with a much greater variety of materials. This in turn would enable the printing of parts under different constraints. We could also make flexible parts out of silicone, strong hardware parts with epoxy, and other things in between. My class group is considering syringe extrusion as a part of our project. This overarching theme could enable a variety of projects which we have not thought about as there has been a limit to the sorts of materials we can use. Therefore I have no practical world projects to suggest so much as I expect the concept of paste extruders has the potential to unlock a variety of new possibilities.

In the end, my interest in syringe extruders is driven by one of my personal philosophies that, when something gets difficult to work with, I like to trade my headache for a new headache. Whether syringe extruders are the be all and end all solution to the worlds' problems or not is questionable, but it will be a different challenge than the one we are working with now. Plus, we could frost cupcakes.

Blog 5: Time

This may be from a while back, but Arduino was first released in 2005. I consider this to be an extremely significant and noteworthy event on the timeline. Arduino makes a lot of projects possible, including 3D printers. Many 3D printers use Arduinos, and many use electronics that grew out of an Arduino such as the Sanguino or Makerbot electronics.

In July 2012, researchers created the first artificial liver using 3D printing technology. This a very important event that marks the beginning of a new era of medicine. 3D printing has the potential to create a world where anyone in need of a replacement organ can get one without being on a waiting list. We have seen the significance of Robohand and how many people it has touched. Imagine what will happen if/when 3D printing can re-create a hand from human tissue.

I added several events to the media timeline. First, in 2007, the RepRap Research Foundation was founded. This was a venture by Zach Hoeken which made 3D printer parts more accessible to people who want to get involved. This event is of paramount significance. Considering the RepRap is made by a RepRap, I remember having difficulty in building my first printer. My first two printers were made out of wood and did not work well. It was the RRRF that really made parts accessible to me and many other people who wanted to get involved but faced the barrier of inaccessibility. This event is worth thinking about. Over the years I have seen 3D printers become much more accessible. It is due to the RRRF and similar ventures that I myself was really able to get involved. When I started to build my first printer in 2006, I could not even afford the electronics because getting PCBs made was too expensive. The RRRF is an often underlooked yet significant game changer in getting 3D printers to people who want them.

In May 2008, the first grandchild RepRap was assembled. This was the second time a RepRap had created another RepRap and it was an exciting beginning to the concept of a RepRap making its own parts. I also added the founding of MakerBot Industries in early 2009. They created the first easily buildable do-it-yourself 3D printer kit and went on to churn out a lot of innovation in the realm of 3D printers.

Blog 4: Reflections

This week I was asked to read the blog posts about the Open Source Ecology project made by my team mates and other class members and note any thoughtful points I did not touch on. I started by reading my team mates blogs. Wenxin mentioned OSE can be used to maximize profit by manufacturers, which I did not think about. I was focusing more on making technologies accessible to people who otherwise could not access them. She also cites efficiency and convenience, offering OSE as a solution in cases where a non-open source machine is not as fit for the job or would be less accessible. This makes me think about how I could use these machines as more accessible forms of machines I use already.

Anthony brings up the point of practicality in a developed nation. I did not mention this directly in my post. He says it would be rather impractical to implement Marcin's civilization starter kit in a developed nation because it requires you to start "from scratch". I would have to partially disagree. I agree it would not be likely to see many people in, say, the United States building every machine he has in the civilization starter kit. However, I believe the project has the potential to make some tools more accessible to people in any country. You do not have to use everything he designs.

Nam and Eva both saw some more positive notes in the New Yorker article. I seemed to miss any hint of a supportive attitude in the New Yorker article, but Nam (while he does call the article a criticism) says the article's discussion of some of the people who tried to participate in the project is true and worth consideration.

Outside of my group, Graham Deever thought service related clubs and groups might be interested in Open Source Ecology to enhance helping people in need. Graham, Kyle Casterline, and Carson Geib all comment that the New Yorker article is unnecessarily critical and overly cruel. I did not make such a remark in my blog. It is my belief that a positive outlook is better than a negative one. However, in this case, seeing this article as extremely critical is entirely accurate. I do not know the motive of the article's author

Lee Schwartz and Kevin Moyer both discuss the potential threat posed by Open Source Ecology to mass manufacturers of these products. I did not consider the reaction of large companies when I investigated Open Source Ecology. With consideration to OSE's open source nature, it would be challenging to fully "shut down" this project, although, like other open source projects in the past, it could be made difficult to access design files and conduct further research.

Blog 3: Robohand

This design is called Robohand, and it was created by Ivan Owen, a designer in Seattle, WA, and Richard Van As, a carpenter in South Africa. You can read more about the project and its origins on their project website. It began in early 2011 when Van As lost several fingers in an accident. This pushed him to want to design something in response, and led to his eventual collaboration with Ivan Owen. In early 2013 Ivan flew to South Africa to collaborate with Richard Van As directly. They were approached by a lady looking for help for her child, who suffered from Amniotic Band Syndrome, a condition which can prevent the proper formation of limbs in newborns. The duo was able to craft a new hand for the child out of metal parts.

Eventually, Makerbot donated a 3D printer to each of them to assist in their design process. One thing led to another and Robohand was born. You can print your own version with their design on Thingiverse, or contact the people who are involved in the project on their website. Unfortunately, the newest versions of their designs are no longer open source and released for free. It is still the goal to make the technology accessible, but the open source nature of the project turned bad.

Makerbot created their own snap-together version of the Robohand. This version was intended for publicity, but some people in the community actually printed it and tried to use it. The real Robohand is designed to be made with stainless steel and medical orthoplastic in addition to printed parts. However, the snap-together version is both weak and liable to cause skin damage and infections if used in the place of a proper Robohand. Robohand gives this information on their FAQ page and uses it as an explanation as to why they had to stop releasing their project designs. If you read this article, at the bottom of the article it describes Makerbot's Robohand as a "new version" and uses that to explain how fast 3D printing improves designs. This is an issue because Makerbot's derivative is not a "new and improved" version, but rather something which confused the community.

Further Reading:

- Article in ArsTechnica

- A video discussing the origins of the Robohand

- Robohand's founders used crowd funding to help their project. You can find one of their crowd funding attempts here

- An article about Robohand appeared on TIME magazine's website

- Robohand appeared on Mashable

Blog 2: Open Source Ecology

When I watched Marcin's TED talk I got the feeling this project has high potential. The Open Source Ecology project is absolutely astounding. I would describe this effort as a positive and potentially world changing effort to put basic technologies in reach of anyone.

There are people around the globe live without houses. Those people have to spend days on end making bricks to build a house. If those people had access to the plans to make an open source brick press, their lives would be changed. Suddenly the basic human need of housing, formerly difficult to attain, is brought within the reach of many people who can now produce bricks faster and spend less time on such a basic need. It frees people. Such is the idea of the OSE project, which aims to free people and empower the world with the ability to build industrial machines and maintain cilvilized living for yourself. They publish fairly regular videos documenting their progress on Vimeo.

The latest update to their development blog was made last November and showcased an open source 100W lasercutter. This effort proves the potential of the project to have a wide scope and that the fifty tools they are developing have the potential to enable you to make anything.

The New Yorker's article was an interesting critique which offered insight into what really happens on the farm Marcin Jakubowski, the OSE project founder, purchased to be the foundation for his open source civilization. A lot of the article reveals appalling living conditions and a lack of work effort on the part of some of the inhabitants. It mentioned comments made by people who had been a part of the project at one point or another. Many cited a lack of skills, stating the project had a lot of interested individuals who were more interested in the idea of the project than they were actually able to help. I find this critique interesting as it reminds me of the idea of the invisible hand in economics. Economists use the idea of the invisible hand to explain why things fall into place - as in why, without someone dictating each thing to do, modern life fell into place piece by piece, owing its creation to millions of people with skills. The New Yorker article pointed out that the OSE project has an ambitious goal with specific steps to get there. I think that by dictating what will happen and what the goal is, it makes the project difficult to achieve in comfortable. I have no doubt that the goal of designing fifty open source machines is achievable, but the idea of being totally self sufficient from the beginning is unthinkable, as the article indicates, because it forces people to live without heat, cooling, clean water, and even food while trying to put together these machines.

Marcin's response to the article clarified the purpose of the project. He redefines the scope of his project, which is specifically to create the fifty open source machines he identified as the basis for civilization. He specifically mentioned that it is not their goal to create a commune or other small community. This was a view that the New Yorker article pushed, but Marcin retorts it as innacurate. The poor living conditions mentioned in the New Yorker article, according to Marcin, are due to his pushing all of his funding into building machines. It is not a lack of resources so much as it is an intentional focus on just the project. Marcin is so focused on his project he is willing to give up conveniences of modern life.

When I think of Marcin's project, I see his goal as giving people access to information, and by extension access to machine tools. I do not think the administration would be willing to support such a thing, but I think the administration should. It would be the goal of our own OSE project to provide access to basic and complex machines to students. Considering this is a university, that seems like a good way to enhance our learning. Marcin stated in his TED talk that he graduated with a PhD and "realized [he] was worthless". Imagine if we had access to practical machine tools now. We could produce things for ourselves, and upon graduation have more confidence in our skills, more self-sufficiency, and a greater appreciation for the skills required to produce products. I cannot think of any specific professors or students who would be interested in this project. However, if I was going to look for allies in such a project, I would identify people with a common interest but different skill sets. I would want people with a variety of talents and abilities, a positive attitude, and the willingness to do work. From the way the OSE project is designed, funding should not be as much of a hurdle as one might think, as we would be building our own machines. Much like building open source 3D printers for $500 or so rather than buying $500,000 stereolithography machines, an open source machine project makes a variety of tools and machines more attainable.

Blog 1: Objects from Thingiverse

Something Amazing/Beautiful

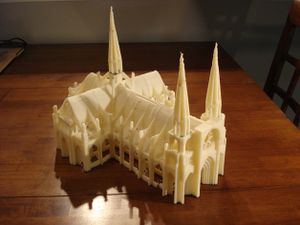

This Gothic Cathedral Playset design was posted to Thingiverse just less than two months before I got my first 3D printer working. I remember how astounding it was that it was printable. At that time it was a huge stretch to be able to make this. 3D printing has come a long way since then but this model remains astounding.

Something funny or strange

Bre Pettis, cofounder of MakerBot Industries, had no idea what he was getting himself into when he uploaded a model of his head to Thingiverse. The Bre of Liberty is just one of many strange mashups made with various objects. If you direct your attention to a Thingiverse search for "Bre mashup", Bre has been mashed up with a dolphin, a bust of Beethoven, and more!

Something useless

This is a printable Cupcake CNC chassis. I do not like to judge other people's work, especially not to the degree of calling someone's work useless. However, my adventures in 3D printing have shown that there is a time and place for every machine. The MakerBot Cupcake CNC chassis was made on a laser for a reason. Printing it out of tiny interlocking squares seems a bit pointless. These large, flat panels are better suited to being made on a laser.

Something Useful

The Robohand project goes above and beyond the call of duty in terms of usefulness. This is an open source, freely available, and printable mechanical hand, designed to be used as a prosthetic. The aim of the project is to make prosthetic devices that are more comfortable than commercial alternatives and more available to people who are missing fingers for any reason.

Something which surprised me

The Pfiercestruder is an interesting piece of work. MakerBot Industries released a paste extruder months prior and began to sell kits in their online store. However, someone without a laser cutter made a printable version! This is surprising because it demonstrates the unexpected resourcefulness of 3D printer operators. Even more so, it surprised me because it was unexpected. MakerBot was putting out products to make a profit, and their community of users was figuring out ways to not buy these products and instead use their home MakerBot printers to print everything else MakerBot has designed.